Fantasy art has always been an interest of mine in conjunction with, unsurprisingly, fantasy literature. Fantasy art now and its short history from the pulp illustration of the early 20th century has its own history which can be examined as a separate entity. Fantasy art after Tolkien and the the advent of high fantasy has become something else entirely worthy of study and obsession. To be honest, I sat down to just do a showcase on one contemporary fantasy artist and found myself drawn to another subject entirely. As much as fantasy art exists on its own, sort of independent from the rest of the art world, at one point it was intertwined. This was in an era before Tolkien and the modern idea of “fantasy” as a genre. In the haze of the western art world in the mid 19th century, premonitions of fantasy floated through art and literature. One of the last full flown daydreams was from a group of British hipsters that thought everything was better way before Raphael.

The Pre Raphaelites were a group of British painters and writers who sought to move away from the high Renaissance compositions lauded over by the Mannerists and obsessed by the 19th century academics. The figurative compositions made famous by the works of Raphael and Michelangelo supposedly clouded the academic zeitgeist and these group of artists wanted to embrace the highly detailed and lush color spectrums of medieval and early Renaissance art. Their rejection of Raphael and his influence gave them their name and these seven artists (James Collinson, William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, Frederic George Stephens, and Thomas Woolner) along with a dozen or so more artist pioneered a small movement which shook the artworld a bit before the whole Modernism thing really got a foothold in the western world. The Pre Raphaelites and their associates are still heralded as masters of daydreaming but compared to what came before and eventually what came after now lie shrouded under slight obscurity save for sporadic coverage. What is interesting about this time period is that things were moving towards one direction and still there was a group gazing longingly to the past.

To be honest, the actual history of the Pre Raphaelites is sort of separate from where my personal interests lie. The whole rejection of an academic focus within the art world in 1840 is charted in the groups’ debates and journal publications and could be of immense entertainment for those with interest in the history of Western art. Where my area of focus is turning is the embrace of the fantastic for their subject matter. With the wave of modernism and realism overtaking Romanticism, these group of artists and associates immersed themselves in a world of their own and rejected centuries of visual innovation. My interest, again, lies in the concept of fantasy before the term fantasy existed. Through myth and fairytale and legend, the works of the Pre Raphaelites contained glimmers of what would be on paperbacks a century later. Whether or not they knew of a future devoted to fantastic subject matter, for now these were a group of time fetishists making medieval looking paintings in the 19th and 20th century.

Talking about the Pre Raphaelites movement is nothing new. You could probably land a pretty decent course or section in any academic university or even find better books written on the subject. What I hope to accomplish is to look at certain paintings from the perspective of a fantasy enthusiast traveling to a time when fantasy and fine art were intertwined. It should be noted that despite me introducing the pre raphaelites, most of the artists connected have loose affiliation. Unlike the works of James Collinson, William Holman Hunt John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the artists and their works discussed are either less famous members or just British painters working around the same time, country and even in the same style. Entire articles could be written on certain artists and their relation to the fantasy genre but for now these handful of paintings may lead you into a secret club of wizards hiding in the realm of high art.

Edward Burne-Jones – The Beguiling of Merlin (1872-1877)

Edward Burne-Jones – The Beguiling of Merlin (1872-1877)

The Beguiling of Merlin depicts the Arthurian legend of Merlin who became infatuated with Nimue or the Lady of the Lake and what eventually became of him. In an abbreviated hodgepodge of the legend, Merlin becomes enamored with a lady who refuses her love until Merlin has taught her all of his secrets. Nimue is depicted as reading from a book of spells and learns magic from Merlin who is entwined in branches and roots. The whole Arthurian legends and mythos plays a huge role in the development of fantasy art where artists were free to immerse themselves in the fantastic depictions.

Out of all of the painters being discussed, Jones is perhaps the artist most closely associated with the brotherhood. It was Dante Gabriel Rossetti who helped shape Jones’ career in art and pushed an already medieval obsessed acolyte into a full fledged adept. Perhaps more interesting is Jones association with translator William Morris whose obsession with medieval texts helped shaped modern fantasy. Jones associations with various friends shaped his artwork which was both rooted in a contemporary sensibility but pays tribute to the medieval compositions of centuries past.

Jones is also interesting to study for his work in the decorative arts, particularly stained glass. In 1861, Morris, along with a handful of Pre Raphaelites members founded a contemporary stained glass company to decorate churches. The decorative style can be seen in Jone’s paintings especially the Beguiling of Merlin. Though the figures stand complete in the foreground, surrounding them are the illuminated writings of roots and flowers. One could imagine Jone’s painting adorning some strange mystical church as a moral tale to be wary beguiling figures.

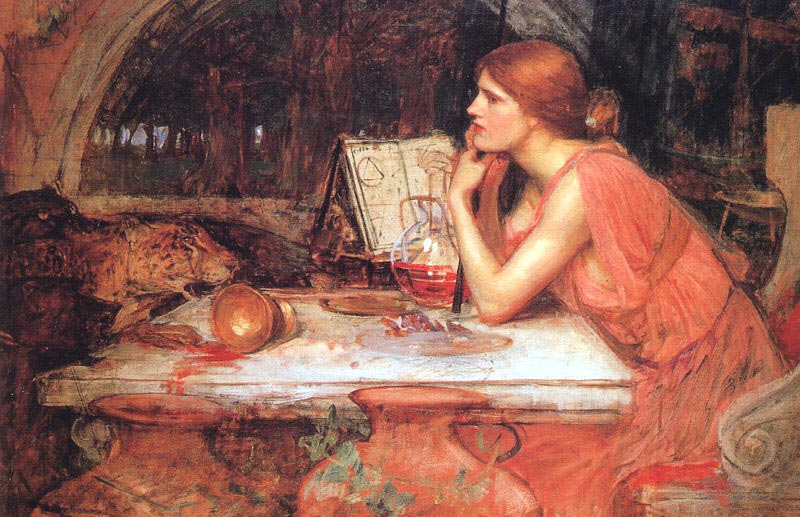

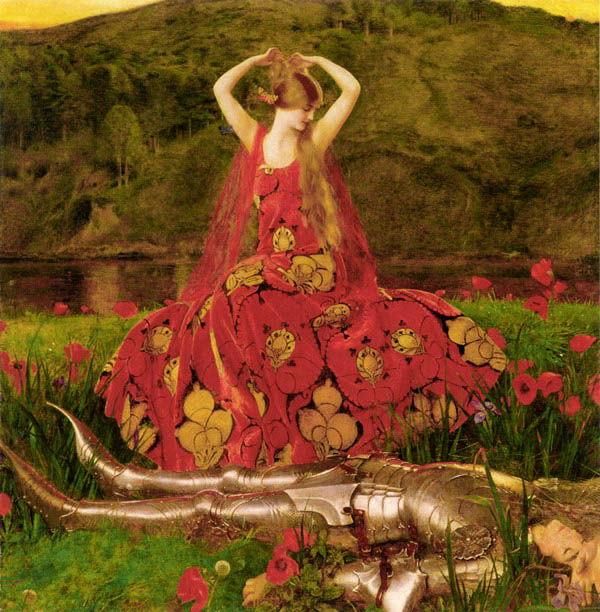

Frank Cadogan Cowper – La Belle Dame Sans Merci (1926)

Frank Cadogan Cowper – La Belle Dame Sans Merci (1926)

La Belle Dam Sans MercI is a poem written by Keats in 1819. In the poem Keats in a roundabout way depicts the tragic fate of a woe begone knight who is at the whims of the Lady Without Mercy. Though no magic is involved directly in text aside from an Elfin grot, its subtext speaks of a classic figure who has come ensnared in the trusting love of a beguiling and unforgiving figure and then left heartbroken alone by a lake. Though there really isn’t one interpretation of the poem though one way of looking at it is in a purely escapist perspective of a knight come to find himself under elvish magic and then abandoned after hellish nightmares. Cowper’s portrayal of the poem one of many paintings illustrating the poem. Additional interpretations comes from Arthur Hughes, Walter Crane and John Waterhouse. Cowper’s illustration is perhaps the least famous with the beguiling female figure towering over a slumbering knight. Her patterned dress is both modern for the time and bewitching. Cowper’s painting also came at a time when the art world was experiencing already the shocks and rumbles of various more intellectual art movements like Cubism, Surrealism, Dada and Impressionism. Cowper’s painting came at a time when few people cared about slumbering knights and for that reason makes it fascinating to behold.

Edmund Leighton – Godspeed (1900)

Edmund Leighton – Godspeed (1900)

Perhaps one of the more accomplished painters of this time period and style was Edmund Leighton. Leighton’s detail and compositions and themes threw themselves back to medieval time periods but retained a classical sense of style. Godspeed, painted in 1900, represents the first of three paintings dedicated to the concept of loyalty and fidelity to service. The Accolade and the Dedication would come later in the decade and all embody a code of honor which given the time period was a grim portent to the events 15 years in the future. Leighton’s works are magical in the sense of being immersive in both medieval and current time periods.

Leighton’s obsession with medieval subjects is perhaps the basis for modern fantasy. Both Godspeed, The Accolade, and various other paintings depict what is suppose to be normal scenes of history. This sort of historic genre painting does not have the sense of imagination like modern fantasy but still retains a sense of romanticism for the past. Godspeed’s celebration of chivalry and heroism does not speak of the horrors of battle rather joy of service and duty. The maiden wishes the brave warrior well as he casts off to fight some unspecified battle. Even though Leighton’s historical depictions lie on the close side of realism, their worlds are entirely constructed and immersive with a sense of heroism running through its center.

James Campbell – Dragons Den (1854)

James Campbell – Dragons Den (1854)

James Campbell is not an artist who has had a lot of work to his name. In fact most of the paintings attributed to this English artist are in fact are diametrically opposed to the themes we have been discussing. Two paintings such as “Waiting for Legal Advice” and News from the Lad are depictions of everyday people engaged in everyday things. This genre type of painting is far from the knights and fairies of other artists discussed. Dragon’s Den is perhaps Campbell’s only fantastic painting and depicts a massive cave mouth with any sort of human or monstrous depictions obscured in undergrowth.

The concept of dragons has existed for centuries but the role of dragons within the fantasy genre has been shaped by later writers. Before they were intelligent and possibly playable as characters, dragons existed as mythic bounty for heroic deeds. Campbell’s painting showcases a small painterly figure breaching the mouth of the cave and in fact has his humans almost secondary to the enormity of nature. For an artist who has thin associations with fantasy, Campbell’s reverence to the themes of the fantastic is quite impressive.

I did not know what I wanted to do with this article when I started. What started as a showcase turned into a slight obsession finding fantasy related artworks in a time when the fantastic was embedded with mythology and history. Most of the traditiuonal artists associated with the Pre Raphelities were not wild in their depictions of fantastic subject rather did their fair share of religious and female subject matter. The study of proto fantasy is much larger than just British painting in the 1800’s and in fact can be the subject of many more articles to come.

Edward Robert Hughes – Fantazie za soumraku (1911)

Categorised in: Art