Arguably one of the most defining films in the Universal horror cannon is Dracula. Actually, come to think of it, Dracula is one of the most definitive horror films, if not characters, in cinematic history. This article is a part of an ongoing Summer series reviewing classic and forgotten horror films of the 30’s and 40’s. The last article was dedicated to Lon Cheney’s portrayal of the masked hunk, aka the Phantom of the Opera. Tod Browning’s 1931 adaptation of the 1897 gothic horror novel Dracula by Bram Stoker is a film that lives in cinematic history. This fact can be attributed to many things, from acting and production, to the reception it received upon release. What is certain however, is that Dracula, as an entity, would not be the same without this 1931 film.

The image of Dracula that we have today is different than one in the original novel. Aside from confusion regarding vampires’ strengths and weakness, the image that we have of the grand count has been shaped by Browning’s film. Rather than a hairy older sharp toothed gentleman described in the Stoker novel, we are given a handsome gentleman. Unlike F.W. Murnau’s 1922 film Nosferatu, Browning’s Dracula retained the same Eastern European description and made it more monstrous. Browning’s film let go of these off-putting features of Dracula and replaced them with a character that was, for lack of a better word, dashing. The Browning film took heavy cues from a 1922 stage adaptation of Stoker’s novel where Dracula was imagined as a more cosmopolitan gentleman than a repulsive hermit. The stage adaptation of Dracula not only made the character more relate-able but ultimately more terrifying as evil came not in monstrous form but rather cloaked in elegance.

It is impossible to discuss Dracula without talking about Bela Lugosi. Bela Lugosi, much like Lon Chaney from Phantom of the Opera, was in numerous films before becoming the face of the villain portrayed. Unlike Chaney, Lugosi had two decades of shaky filmwork previously that oscillated between primary horror, comedy films, and second rate productions. Lugosi would maintain a rivalrous friendship with actor Boris Karloff before seeing his own career famously spiral down, ending in the productions of Ed Wood. Though Lugosi fought for years against the villain that typecast his legacy, he is the man that has summed up the character with a terrible accent and cartoonish gestures. I feel the actor owes this legacy to a time and place within history where audiences were waiting for the villain they could alternately embrace and recoil at.

Alright, we need to seriously review the protocol for where patients are allowed to go. This guy just appears everywhere. Yes, I know. Rats. I heard it before.

When discussing old horror films, especially ones based on now classic novels, it is difficult to assume how much the audience knows. By 1931, it is assumed that the Stoker novel was at least popular enough to incur multiple, sometimes illegal adaptations. The Browning film assumes a lot by holding back sometimes needed exposition to inform the audience what is happening in the story. While this may be just a product of early cinema, Dracula, as a film, is steeped in slow moving mystery. It assumes you know the major players and, possibly, how they switch places on stage. For anyone who seriously does not know the plot, Dracula could easily be transformed into a romantic comedy about a lonely Eastern European aristocrat moving from his home only to find himself a fish out of water in London. Everything soon makes sense for “Vlad” as he finds the woman of his dreams, Mina, but gets mixed up with trouble when her fiance, John, and a crazy ol’ professor / vampire hunter named Dr. Van Helsing get in the way.

Dracula succeeds as a film not because of its faithfulness to the text rather its structure in early cinema. Much of the the pace and tone seen in Browning’s film was first presented in Hamilton Dean’s 1922 stage adaptation. Rather than the novel’s central character, Jonathan Harker, traveling to the Carpathian mountains to do the worst real estate deal in history, it is the (soon to be loony) R.M. Renfield, who ignores all advice by the villagers and travels to the Dracula estate. Renfield’s more pivotal role in the plot is important, as his portrayal by Dwight Frye is perhaps one of the most entertaining aspects of the film. Renfield’s mania contrasts the cool and almost silent portrayal of Dracula. Renfield is chaotic, unsure, and driven by desire and shame. Dracula is his complete opposite even though he is on the same side of evil. This change in a central character of the novel makes more sense cinematically and allows for added performances that would have been left out. Browning’s adaptation allowed for the story to be translated into a new medium which because of its versatility, created a film that resonated well with its audiences.

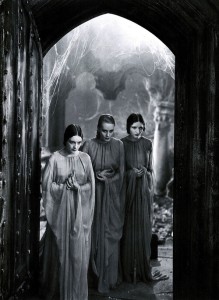

The weird sisters or brides of Dracula represent worlds of mystery due to their nonexistent role in the story. They also bring up some really weird questions of vampiric incest and polygammy.

Browning’s changes also worked the other way. Jonathan Harker, who originally was left in the Dracula mansion at the mercy of Dracula’s concubines but soon escapes to become Mina’s main interest, is pushed back to a side role in the film. When on screen, Harker is a stuffy whining child who contrasts the debonair attitude of Dracula. In the novel, Mina’s friend Lucy was originally weighing three suitors who would later become some sort of super vampire killing team that took down Dracula in his castle. The Browning film omitted two of her suitors, Arthur Holmwood and Quincey Morris, changed her third suitor, Dr. Seward, to an old Doctor of the asylum, and made Mina’s Jonathon Harker a sniveling twerp. What does all of this trimming and reductions give us? More on screen time in which Dracula stares at the audience with dead evil eyes. Cinematicaly, the excess which originally made sense in the novel is reduced to allow terror to unfold in abject silence.

One of the most striking aspects of the film is the complete absence of a score. Music and dialogue integration were at their most primitive stages in early cinema and a lifetime of having those two elements intertwined gives way to a stark experience when taken away. Though Philip Glass did a fabulous retrofitted score with his Kronos Quintet in 1999, Dracula succeeds in its silence and is, perhaps, more frightening because of it. The long pauses between dialogue and action are wrought with tension and a low hum of production noise. Pieces of dialogue are now dotted islands in a ever growing sea of nothingness. This is what makes the dialogue from Dr. Van Helsing so reassuring or the tormented please of Mina more terrifying. It is an attribute that has only grown in its being obsolete. Rather than being something to rib comedically, the silence in Dracula has created something so unexpected that the sheer accidentalness of it is ever more frightening.

I do not want to leave here with one thinking that the 1931 film scared me in the same way that Paranormal Activity, The Shining, and Wait Till Helen Comes did as a child. Browning’s film has a silly looking rubber bat that is used as a centerpiece to the horror. It is not scary and is as obsolete as the aforementioned silence. Classic films must be judged by their merit as a film released in the past but also as on ongoing entity. There are things from the 30’s that are just not scary anymore. There are others, however, which will continue to live in history and forever stalk the night with dead eyes.

Tags: Classic Horror, Dracula, Film Review, Hollywood Metal, Kaptain CarbonCategorised in: Film